- Home

- Articles

- Trading Card Spotlight

- Science Fiction Trading Card Spotlight - Catherine Asaro

Science Fiction Trading Card Spotlight - Catherine Asaro

Our next Science Fiction Trading Card Spotlight features Catherine Asaro, who is displayed on card number 78 from the Science Fiction Collection. Catherine is an award-winning writer on such genres as science fiction, fantasy, and near future thrillers. She is best known for her Ruby Dynasty series, which has won her numerous awards. Such awards include the Nebula for her book, The Quantum Rose, and her novella, The Spacetime Pool. Catherine suffers from stealth dyslexia which can make writing challenging for her, but for the first time ever in public she is expressing her feelings in this interview about it. Catherine hopes to make a difference helping others with stealth dyslexia to follow their dreams and do what they love.

How early in your life did you know you would be a writer?

I started making up stories as soon as I could imagine worlds, sometime around age two or three. That included the tales that eventually became my books. Of course, the stories were different then, less sophisticated, innocent, just youthful adventure about a girl going into space with her cat. They evolved as I matured, with handsome space pilots replacing the cats, but I didn’t start writing until college. I wrote my first book at the end of my undergrad years—and it took over. I didn’t want to stop. I did stop in grad school, because I knew if I kept writing, I might never finish my doctorate.

Also, I wrote that first book by hand, which I found excruciating. I knew what I wanted to do with the manuscript, how I needed to mold it, rewrite, revise, add to, delete, or sculpt the prose. For me, the writing process required a constant evolution of the text. It was impossible to do by hand. I finally put it away, thinking I’d come back to writing in the future.

Some years later while working on my dissertation, I needed a break, so I started doing fiction in the evenings. At that time, word processing was in its infancy. I had one of the first PCs, a Heath Zenith kit with 32 K of memory (I upgraded to a whopping 48 K!). Now I could write on the computer and mold the text the way I’d envisioned for my first book, which by then was buried in a box, never to be seen again. I had to save my work on multiple disks, those big floppy ones about eight inches in diameter, but I could mold the text using a Peachtree word processer.

And so. That was it. The writing took over. I finished my thesis and was a physics professor for a few years, but I knew I wanted to write. It wasn’t as if I chose writing. It chose me. I had to do it. Eventually I decided to write full-time, and I resigned from my academic position.

How has writing today changed from when you were younger? What do you like or dislike about the changes?

For me, the biggest change came with computers. I doubt I could have become a writer like I am now without a word processor. I certainly wouldn’t be as prolific. I find writing long pieces by hand painful. I practiced cursive script a lot as a child, thinking of it as an art rather than written words, so I can write beautifully when I take the time. But it’s a strain. When I write on the computer, I’m always revising, adding, deleting, molding the text as if it is a visual creation on the screen. I see it all at once, an interactive word creation that I’m sculpting. You can only do that with a computer.

The reason I do it that way has to do with another change. People now understand the learning challenge called stealth dyslexia. I never knew I had dyslexia until I reached my fifties. The term “stealth” wasn’t even coined until around 2005. It’s called stealth dyslexia because it’s rarely diagnosed. Although students with it perform below their ability, teachers don’t see it because the students pass their classes, maybe even perform at a gifted level. No one realizes they need help.

My mind is apparently wired for math. I can solve problems like nobody’s business, but words are more complicated.

When I found out I had dyslexia, I finally understood the “quirks” in my writing, like how much I struggled to do it by hand, that I required a word processor. I realized why I needed to see the entire page on the screen. It is how I absorb text, as a whole rather than word-by-word. I’d always felt ashamed that I was a terrible speller despite my huge vocabulary, despite my being a writer for heaven’s sake. It turns out that is a well-known trait of stealth dyslexics. The knowledge that my writing process came from a difference in the way I learned allowed me to let go, to stop thinking “I should be able to do this or that because everyone else can.”

I’d already written more than twenty novels by then, so obviously I learned to compensate. It turns out many of the mechanisms I’d come up with were known as methods for coping. Understanding why I’d struggled all those years let me make peace with my differences. I’ve become a better writer since then, perhaps because of more experience, but also because I’m no longer trying to fit a more traditional mold. If anything, the process I developed over the years makes me a better writer. I’m always revising, studying my word and phrasing choices, going over the text to see if I can make it better, smoother, more evocative. I’m grateful that it works, because I love writing.

You've become well-known as a writer. How did you learn coping mechanisms?

It started in first grade, when I went from well below average reading for my age to several years ahead within a matter of days. It happened because I wanted to read my older sister’s book from her class, and I got so wrapped up in the story, I finished it in one afternoon. Then I went looking for more to read. My teachers and parents didn’t know what to make of it. All I knew was that I’d turned a corner. Suddenly reading had gone from painful to easy. I loved it.

Except, that applied to fiction. I realize now that I taught myself to speed read so I didn’t have to go word by word with the text. I read by groups of words instead, absorbing the meaning of a phrase without deciphering each word. So yeah, I read fast. I can’t do that with technical writing because if you miss even one detail, it can give birth to disaster. Consider this sentence: “The flow of heat isn’t constant.” If I read too fast, seeing it as one statement rather than individual words, I might get, “The flow of heat is constant.” Only one word slightly misread—but it reverses the meaning. For fiction, I don’t make as many mistakes, it’s less technical, and any mistakes I do make usually get fixed because the context makes the meaning clear. For technical work, it creates a huge difference.

I also make those mistakes with email, which means I must constantly reread messages and check my answers. I continually misspell or leave out words. It’s why I’m always behind in answering people. It can take me an hour just to get through a simple message. Text on a phone is even worse. If it wasn’t for voice recognition, I couldn’t do it. However, I can’t see more than a few words of the texts on my phone, voice recognition programs mess up words even more than I do, and editing is excruciatingly slow. I’m constantly sending people weird texts with strange mistakes.

During college, both my undergraduate years at UCLA and my graduate years at Harvard, I never finished the required reading for any class. I thought I was lazy, I had bad study habits, I should “just” read faster. I recently looked at one of my old textbooks, and it stunned me to see the coping mechanisms I’d used, underlining, or highlighting substantial portions of text to help me focus on its content, writing notes everywhere, and constantly putting “goov” in the margin for underlined material, which meant “go over” passages I knew I hadn’t absorbed well enough. Well, I never had time to goov anything.

I didn’t give up because I loved learning. Math and science came more easily. Those subjects are oriented toward problem-solving, my forte, so I didn’t have to finish the reading to figure out most of what I needed to know. I would solve numerous problems and learn from those. However, I enjoyed most every subject I took. So, I found ways to cope. Organic chemistry stymied me until one of my profs told me to stop trying to derive all the syntheses from first principles. He said, “Make flash cards. Memorize. There’s no shame in doing it that way.” So, I did. And it worked.

I wish now we’d known about my form of dyslexia, so I could have received some help rather than learning to cope through trial, error, and luck. I was fortunate to be born in this age. I can’t help but wonder how many scholars our civilization has lost because they didn’t have the technology they needed, like a word processor or voice recognition, to overcome a learning challenge.

That form of dyslexia sounds like it’s difficult to detect. Where can readers find out more?

Here are a few web sites.

Quantum Leap: Peer Monitoring with ASD

I discovered the research into stealth dyslexia years ago during a literature search. I was trying to understand why a student of mine with an extraordinary gift for math struggled to write his solutions. He made errors he knew were wrong, but he often didn’t see them until after he turned in his work and missed a problem he knew how to do backward, forward, and upside down. Although that happens to a lesser extent for many students, this was at a level beyond what I’d seen, and for a brilliant student who had the potential to be one of the tops in the country.

Reading the work on stealth dyslexia turned out to be a real eye-opener. It also described me! So, I looked into it for myself as well as my students.

How did you feel when you realized why you had always struggled?

I cried the day I accepted that I had a learning disability. I wasn’t a screw-up, a failure, forever incurably lazy. I had a well-understood learning challenge.

I do like to read. For some reason a story with characters and a plot is easier to absorb. By the time I was eight or nine, I’d gone through every sf and fantasy book in the children’s section of the local library, so the librarian gave me a card for the adult section. I was like a kid in a candy store. I used to come home with six or seven novels, Andrew Norton, Isaac Asimov, Ursula Le Guin, Robert Heinlein, Zenna Henderson, Madeleine L’Engle, Fred Pohl, Leigh Brackett, Arthur C. Clark, and so many others. I’d devour them in a few days. I thrived with that library card.

I read technical materials too, and greatly enjoy them. It just takes longer. Fortunately, I have a good memory. I tend to remember the technical material better than fiction because I have to concentrate more and go slower as I read.

However! I never had trouble with math. I love problem solving, and I’m really, really good at it. Doing math is like drinking water on a hot day. Sometimes when I want to relax or relieve stress, I solve math problems and draw pictures of mathematical functions. It’s no coincidence that my doctorate, masters, and BS are all in the application of the mathematical methods of physics, in particular to describe quantum systems. It’s gorgeous math.

Does your work outside of writing, the math and science, affect what you write?

Very much. I always end up writing science and math in my stories, more so in some books than others. As a result, some of my works are considered hard sf and others are considered softer. Some readers think my fiction isn’t hard sf because my focus is first and foremost on characterization, world building, and the quality of the prose. However, I can’t help but add science and math even when I’m not aware I’m doing it.

One of my “softer” novels, the Nebula-Award winning The Quantum Rose, is an allegory to quantum scattering theory. It’s also a retelling of Beauty and the Beast in an sf setting. I described the allegory in an essay at the end of the book rather than in the text. In the original version, the essay has problems because I ran into the deadline for the book when I had just started writing it. So, I had to turn the book in to the editor with the essay unfinished and sloppy. However, I’m currently rewriting that book for re-release in e-book form, so I’m spending time with the essay, making it easier to read, clearer, smoother.

I named another of my books, Spherical Harmonic, after the functions of the same name that appear in physics, including the quantum description of atoms and molecules. The book uses powerful mathematics to describe the journey of the heroine, the Ruby Pharoah, as she regains her throne after a war. The text even has prose poems in the shape of the curves.

Years ago, I choreographed a ballet en pointe for four dancers called Spherical Harmonic. It’s all flowing motion. The music is Eric Satie’s Gymnopédie No.1. The dancers wear the colors I see for the harmonics. In my mind, I’ve always perceived colors and textures for numbers, letters, equations, and the functions created from those equations. The spherical harmonics shimmer in a pastel space, lovely curves in rose, lavender, blue, and silver. For the ballet, I had the dancers wear leotards, tights, and flowing skirts in those colors and move through space in waves.

One note: Ballet dancers tend to excel at math. I danced in my youth, starting around five and going well into my twenties, ballet always, but also some jazz and modern. I reached a professional level and ran a dance troupe for a few years. I discovered many dancers I worked with also found math easy. It isn’t surprising, though it may seem so at first glance. We’ve long known classical music and math go together well. Dance, especially ballet, includes that aspect but goes beyond it. Dance is patterns, algorithms your body learns, counting, series, geometry, spatial perception. You absorb those concepts so well that they become innate, part of how you move.

You also learn to envision the arrangements of other dancers in motion. You have to. If you’re a choreographer, you need to visualize the movement of your dancers through space. If you’re a dancer, you need to know where everyone is, so you don’t crash into them, especially when you’re moving fast. It’s all spatial perception and patterns. It’s no surprise many ballet dancers turn out to be good at math.

If you did not become a writer, what would you be doing?

I probably would have remained a physics professor, doing theoretical research. I’d also have worked to further to entry of women and minorities into STEM fields. I do that anyway, but I would have been more directly involved with academics if I had remained an academic.

On the other hand, I might still be running the Chesapeake Math Program. I retired from math and teaching a couple of years ago so I would have more time to write. I did love to run CMP, though. I worked with students as a coach, teacher, and mentor. I also helped various schools establish math clubs, after school programs, and so on. I had some extraordinary students, including several who went on to become honorable mentions or winners of the USA Math Olympiad.

I started CMP a few decades ago when I homeschooled my daughter. She tested ready for college in fifth grade, especially in math. Neither she nor her father and I wanted her to enroll fulltime in college, so I taught her at home (she was a prodigy in both math and ballet and danced with a professional troupe at age 13). Eventually she went to Cambridge in maths for her undergrad and master’s degrees, then earned a doctorate in math from Cal Berkeley. She’s now a postdoc at the Simons Center for Geometry and Physics in Stonybrook.

Are you still involved with writing today?

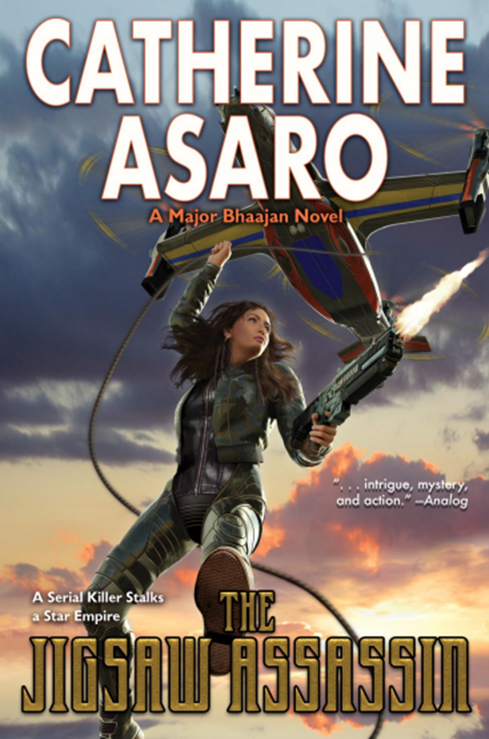

Yes, I’m still writing. I just finished The Jigsaw Assassin, another mystery in the Major Bhaajan series. It should be out this year (cover art by David Mattingly, 2021)

II’m working on a collaboration for two writers who have passed, a popular science book on black holes by two NASA scientists, Neil Gehrels and John Cannizzo (my late husband). I’m also finishing a fantasy novel by Aly Parsons, who was one of my best friends in the writing community before she passed and left me her book to complete.

I’m also getting my backlist in order and hope to have many of the books reissued in the upcoming year or two.

Did you ever think when you were younger you would be on a trading card?

I never imagined! My brother collected baseball cards, so I always figured cards were only for sports figures. I get a real kick out of being on a trading card as an author.

Have you ever received any media coverage for your appearance on the trading Card? If so, where?

It was presented it as part of my Guest of Honor appearances at Balticon 2018. Also, there was a ceremony at Worldcon around that time including several of us who had new cards. It was a real treat to participate in both.

If you could describe Walter Day in one word, what would that word be and why?

He’s a treasure to the science fiction and fantasy genres. Well, okay, that’s ten words. Let’s say “Treasure.” What he does with these trading cards is irreplaceable. It’s a visual history of our genre, one easily held and enjoyed. I can’t think of anything else like it for writing. And that’s just the cards. His career with video games amazes me. His work is genius, and we all greatly appreciate his contribution to the field.

If you could design your own video game, what would it be about and who would be the main character?

Someday I’m going to write all the rules of the game Quis, which plays a big role in several of my books, especially The Last Hawk. It’s played with dice in polyhedral and polygonal shapes, also some special shapes. Several of my readers have asked if they can work with me to make a game out of it, first a board game, then a role-playing game and eventually a video game. Players could choose among characters from my books or perhaps create their own character. I’ve always meant to do work on that project, but I’ve never found time with everything else I have going on. Someday one of my readers may succeed in prodding me into buckling down on that project, or I may kick myself into action.

What do you see yourself doing in the next 10 years?

Writing!